From the early days of vaccination, a desire to remove the threat of infectious disease has been coupled with an ironic hostility to the very medical advances that could achieve that end result.

“The…compulsory health legislation in mid-nineteenth-century England was a political innovation that extended powers of the state effectively for the first time over areas of traditional civil liberties in the name of public health.”

Dorothy Porter and Roy Porter1

Even during Jenner’s time, it quickly became clear that the promise of immunization could not be translated into public health without addressing integral motivating forces of human society. These include such fundamental drivers as reasoning (why take this action?), ethics (should this action be taken?), legality (is this allowed, — or more specifically for this discussion — why is this allowed?), and emotions (does this action feel right?). Key factors contributing to an individual’s hesitancy or outright resistance to vaccination include fear of the procedure and the potential outcomes (a generalized mistrust of science to benefit self) , complacency, (not seeing the need for or value in protecting against disease with a vaccine), and availability (the financial and logistic aspects obtaining vaccines). Unlike those with ‘vaccine hesitancy’, the people who actively oppose vaccinations are commonly called “anti-vaxxers.” The forces listed above that drive behavior, when coupled with individualistic prompts, help frame an understanding of the anti-vax ideology.

The Age of Reason and Mistrust of Science

Long before the current climate of suspicion of experts, scientists struggled to change medical practice to benefit from newly discovered insights. Ignaz Semmelweis fought to institute hand hygiene in surgeries2, John Snow warned against using certain contaminated wells during a cholera outbreak3, and Jenner gave his vaccine away for free4 – all to encourage behavior they recognized would result in better health. People resist change despite unambiguous scientific evidence for a new medical procedure. Vaccination faced the unique challenge of generating protection in healthy individuals by first – mildly– hurting them. The potential to be harmed shadowed the adoption of vaccination, particularly in the early days when Jenner’s smallpox vaccine used pus passed from one person to another and occasionally also transmitted diseases like syphilis5. People naturally questioned the safety and the efficacy of the vaccines, but ultimately vaccination carried less of an imminent personal threat than the disease it prevented (and the diseases inadvertently transmitted). Yet as success of vaccination became apparent, the impetus to act became less acute: the race became not one to defeat disease but to instead install public faith in the new procedure before naysayers directed public focus on the inevitable but rare individual safety exceptions to be found within a diverse human population and to any missteps due to manufacture, distribution, and administration of vaccines.

Ethics and Complacency

To submit to vaccination requires that an individual substitutes the fear of disease for the lesser fear of side-effects. For many people, the cost of the action (vaccination) does not override the instinct for inertia, in part because of the emotional burden of culpability for making a bad decision (which particularly plagues parenthood). A discussion of benefit/risk ratio does not alleviate this innate sense of vulnerability. Add to this a parental protectiveness, and the moral high ground appears to be clear: do not cause immediate harm (in the form of a shot, or when there is a potential for any side-effect). Such myopic arguments ultimately place both the individual and the community at risk of preventable infectious disease.

In contrast to individual protectionism, an early religious rejection of vaccination forfeited all ethical responsibility by evoking God’s right to cull the undeserving.6 Neither of these ideologes addresses the ethics of denying an individual or population the benefit of proactive disease-reduction. Instead, both only focus on resistance as a right. The legal legitimacy of this argument will be explored in the section on ‘Decoupling Health and Responsibility,’ below.

Legality and Availability

“The Vaccination Acts and the Contagious Diseases Acts suspended what we might call the natural liberty of the individual to contract and spread infectious disease in order to protect the health of the community as a whole.” (Nineteenth Century England)

Dorothy Porter and Roy Porter1

Pitting personal liberties against public health engendered the early and vehement anti-vaccination groups. Such battles played out in the legal forum when vaccination became compulsory in England in the mid-1800s.1 The government had assumed the right of protector of the people due to early failure of vaccine programs operating through the first Vaccination Act in 1840, which had been administered by the Poor Law Guardians and resulted in “flagrant evidence of unskillfulness”.1 The law provided free vaccination for the poor to overcome the ‘convenience’ aspect of resistance but had not been designated for medical management.1 Shifting the responsibility to federal offices helped with regulation and supervision of immunization, but also prompted immediate resistance from those advocating for their medical liberties and intent on “dislodging the network of Government control”.1

By definition, “societies” are created when people decide to live in community, and societal rules provide the framework for peaceable and productive coexistence among the participants. These rules do not emphasize individual rights because of the assumption that each member can chose not to be in community. This default no longer applies as it is virtually impossible to live outside any civilization, which means that the focus has shifted, and the desire to demand certain individual rights now dominates many modern political discussions. However, rules contributing to fundamental social existence must be imposed and, once codified, are an expected part of the group pattern of behavior. These rules include a prohibition against stealing and murder, for instance, but also cover such mundane things as stopping at red lights at intersections. A societal cornerstone is that the rights of individuals do not include the right to unilaterally hurt others. Vaccination quickly became a political tinderbox because the personal act of being vaccinated could be viewed both as an individual choice and a societal responsibility. Today, anti-vaxxers continue to challenge requirements to become vaccinated despite an underlying mandate in society that favors protecting the populace rather than personal privileges.

Emotion

Science understanding, ethical considerations, and legal aspects of vaccination generate debate and at some level are susceptible to persuasion, but the emotional impact of medical decision-making is not influenced through intellectual discourse. The inability of facts to persuade people to change behavior is a well-known and much discussed phenomenon.7

Fear spreads faster than relief.

The anti-vaccination movement developed, primarily, from fear of change, of the unknown, of pain and sickness. Rejecting vaccination or choosing inactivity when faced with the threat of disease seems counterintuitive but can be a way to renounce responsibility and a subsequent sense of guilt. People inclined to emotional rather than logical decisions are also disposed to go down the rabbit holes offered by the anti-vaxxers, whose literature propagates myths, conspiracy theories (notably about Big Pharma), and scientific misinformation.8 Particularly potent are the misinformation campaigns linking immunization with unrelated disease outcomes, especially those diseases with unknown origins and with dreaded outcomes.

Decoupling health and responsibility

The anti-vax movement fosters two main tenets, examined below. Both serve to decouple proactive decision-making from medical responsibility or, in other words, they help: 1) absolve parents of guilt for causing their child harm by a rare side-effect from vaccination (though, ironically, not from contracting the targeted illness), and 2) support personal liberty at the expense of public safety.

- Anti-Vaxxers allege that vaccines are not safe.

Arguments about immunization safety often follow a pattern.8 Despite the lack of scientific evidence, a concern gains traction in the public conscience by linking a condition of increasing prevalence or unknown cause to vaccination. The initial study or studies have inadequate methodology. Premature reporting occurs in a widely-viewed way due to yellow journalism or amplification by sympathetic social influencers. Increased awareness of the unsubstantiated claims fosters a positive feedback loop by resonating with individuals suffering from the condition that is thought to have been caused by vaccination, amplifying a sense of urgency and incidence, and spurring trends in social media that create echo chambers. The ensuing tribalism forgets, neglects, or underestimates the potential harm of forgoing vaccination and focuses on only the perceived harm. The social harm is done; it takes several years to regain public confidence in the vaccines.8 (Interestingly, “in almost all cases, the public health effect is limited by cultural boundaries” which belies the anti-vaxxers’ stance that they have scientific proof: “English-speakers worry about one vaccine causing autism, while French speakers worry about another vaccine causing multiple sclerosis, and Nigerians worry that a third vaccine causes infertility.”8)

In unraveling the underpinnings of the modern, English-speaking anti-vax movement, two people play unreasonably prominent roles. Both Andrew Wakefield and Jenny McCarthy promote the unsupported claim that the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine causes autism.8,9,10 In science, causal relations can be directly tested and verified. Unfortunately, a negative relationship cannot be proven. This means that once an association is made and a causal relationship claimed, the science necessary to refute it relies on multiple inconclusive studies. Scientists are reluctant to search for a relationship that is not there because it “is not a particularly interesting story to tell”.11 Moreover, funding for these scientific investigations diverts research time and funding that could be used more productively elsewhere. The alleged claim of harm by vaccination seems to go unrefuted by the science community.

News reports do a disservice to both scientists and the general public by reporting alleged associations before studies show conclusive evidence they exist.12,13 People tend to accept as fact what they hear or see in the media. The studies that indicate a lack of causation can take years to amass. This time lag allows unimpeded promotion of the false link.

In the case of MMR and autism, Andrew Wakefield was the lead author on a paper published in the Lancet in 1998 that implied a causal link of the vaccine and the development of autism combined with inflammatory bowel disease in twelve children.14 Numerous issues riddled the published research, including: 1) study design: this study relied on parental recall with no control group; 2) small sample size: a study group of twelve children is considered unsuitable for discerning associations let alone causation; and 3) timing: the diagnosis of autism often occurs around the time children are receiving their vaccines.15,16,17 Furthermore, the lead author wrote the speculative conclusion without reporting his conflict of interest in the outcome. When it was uncovered in 2004 that he had received funding from litigants against vaccine manufacturers, the Lancet published a short retraction of the interpretation of the original data by 10 of the 12 authors.15 Finally, in 2010, the Lancet completely retracted the paper based on the ethical grounds for the way the research itself was conducted as well as evidence of patient data manipulation. In addition, Wakefield was barred from practicing medicine in the UK.

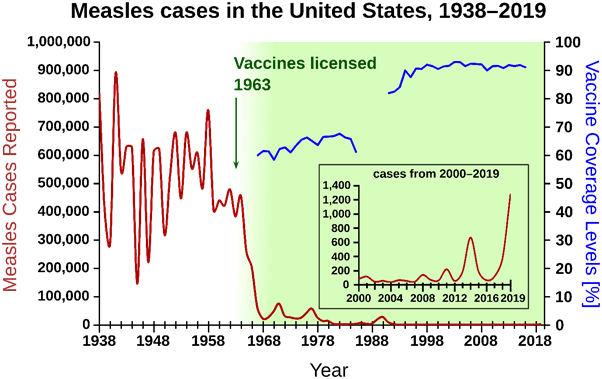

Wakefield’s implication that there was a link between MMR and autism was enough to create an uproar. Vaccination levels declined in the years following the published article, and tens of thousands of children were put at risk for the diseases preventable by MMR vaccine.6 (See figure, below.)

“The Wakefield fraud is likely to go down as one of the most serious frauds in medical history.”15

Meanwhile, in 2007, actress Jenny McCarthy began condemning the MMR vaccine for causing her son’s autism.18 Emotional appeals of a personal nature tug at anyone’s heartstrings, and her visibility provided a particularly significant platform for the anti-vax message. McCarthy authored three books on autism and helped organize a movement of parents about a vaccine-autism link. Her social position as celebrity, author, and activist resulted in undue influence against vaccination, despite federal and national scientific institute communications to assure the public that there was no credible link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The lack of confidence in MMR has damaged public health.

People want to believe an individual’s anecdotal narrative over abstract, complex scientific narrative.

The influence of these two people has disproportionately swayed public attitudes against vaccination and provided momentum to the anti-vax movement. The perceived but false relationship between MMR vaccine and autism continues today despite a large number of research studies that have not found a link.19 Considerable taxpayer money has been spent to clarify for a suspicious public that the MMR vaccine is safe. One legacy of anti-vaxxers like Andrew Wakefield and Jenny McCarthy is the unnecessary scientific focus on trying to ‘prove a negative’. The most significant legacy, however, is their contribution to a climate of distrust of all vaccines and the reemergence of other previously-controlled diseases, resulting in various epidemics and deaths.20

Overwhelming scientific consensus about the safety and efficacy of vaccines invalidates arguments against vaccination.8

2. Anti-Vaxxers value personal choice above public health.

The issue of the rights of the individual versus the rights of the populace has significant ethical considerations. How these ethical considerations played out in history impacts vaccination laws and procedures today. In 1853 and 1867, the UK passed mandatory vaccination laws that fueled opposition by those who “expressed fundamental hostility to the principle of compulsion and a terror of medical tyranny.”1 This early anti-vaccination movement was met with a political response: a commission tasked with studying vaccination efficacy ruled that vaccines protected against smallpox, yet the same committee also recommended removing penalties for failure to vaccinate.1 Not only did this concession legitimize the anti-vaccination stance, it emboldened a sense of personal entitlement that allowed exemptions for certain groups of individuals within society. Significantly, this ruling paved the way for a subsequent law that allowed conscientious objectors to opt out of mandatory vaccination programs.1 Since then, many scientific and medical research studies have found that individuals who exercise religious and/or philosophical exemptions are at a greater risk of contracting infections, which put themselves and their communities at risk.21 Although the early political actions helped mollify subgroups within a disgruntled public, a precedent was set; namely, that ethical considerations of an individual could be imposed on the group. At the time the law was passed in the U.K. in 1898, it fell to the local courts to distinguish between true objection to vaccine and mere neglect.1 The democratic process was overridden and a minority wedged a legal concession into the public health protocols.

It seems morally appropriate and entirely within ethical rights that individuals chose for themselves and their children whether to submit to a medical procedure, but unlike most medical interventions, vaccines prevent diseases that spread to other people. At the same time that anti-vaxxers claim “my body, my right,” they indicate their willingness to subject others to potential danger. The resistance to vaccines has less to do with individual health than it does with protecting individual choice. A recent report shows that mandatory vaccination fuels anti-vax sentiment to such a degree that no benefit in population health was seen compared to countries offering voluntary vaccination.22 This result is described as a backlash to an overprotective state undermining individual responsibility.

“Having the government order them to do something reinforces conspiracy theories, and people perceive their risk to be higher when it’s not voluntary.”

Daniel Salmon, director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety at Johns Hopkins21

The argument continues to reverberate today: does population health trump an individual’s liberty to make personal medical decisions? A landmark legal precedent was set in the U.S. in 1905. At that time, the city of Cambridge, MA required vaccination, but a citizen named Henning Jacobson refused, saying it was “his right to care for his body how he knew best”.19 Criminal charges were filed against him. Ultimately, the case went before the Supreme Court, which ruled that the States had authority to protect the health of the public in the event of a communicable disease.23 The legal mandate is clear, but as with all things social, implementation requires public support.

Past and future vaccination successes

Despite the anti-vaxxer movement to repel the medical advance represented by vaccination, the success of Edward Jenner’s vaccines proved a scientific ideal: that humankind can eliminate an infectious disease. The world no longer faces smallpox epidemics. However, vaccine hesitancy was identified by the WHO as one of the top ten global health threats of 2019.24 The motivating forces within our diverse human family both drive and stymie behavior that changes the medical landscape. Understanding what shapes our health decisions, coupled with a strong drive to achieve rational outcomes, will allow future populations to embrace and benefit from medical achievements.

“The emotions and deep-rooted beliefs –whether philosophical, political, or spiritual—that underlie vaccine opposition have remained relatively consistent since Edward Jenner introduced vaccination.”19

References

1. Porter D. & Porter R. (1988). The Politics of Prevention: Anti-vaccinationism and Public Health in Nineteenth-Century England. Medical History, 32(3), 231-252. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025727300048225 2. Leighton, L. S. (2020, Apr 14). Ignaz Semmelweis, the doctor who discovered the disease-fighting power of hand-washing in 1847. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/ignaz-semmelweis-the-doctor-who-discovered-the-disease-fighting-power-of-hand-washing-in-1847-135528 3. Tuthill, K. (2003). John Snow and the Broad Street Pump. Cricket, 31(3), 23-31. https://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/snowcricketarticle.html 4. Riedel S. (2005). Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 18(1), 21-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028 6. Hussain A., Ali S., Ahmed M., et al. (2018). The Anti-vaccination Movement: A Regression in Modern Medicine . Cureus 10(7): e2919. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2919 7. Kolbert, E. (2017, Feb 19). Why Facts Don’t Change our Minds. New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds 8. Vaccine Hesitancy. (2021, Feb 27). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Vaccine_hesitancy&oldid=1009102330 9. Einbinder, N. (2019 , Apr 29). How former 'The View' host Jenny McCarthy became the face of the anti-vaxx movement. Insider. https://www.insider.com/jenny-mccarthy-became-the-face-of-the-anti-vaxx-movement-2019-4 10. Hoffman, J. (2019, Sep 23). How Anti-Vaccine Sentiment Took Hold in the United States. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/23/health/anti-vaccination-movement-us.html 11. Tsou, A., Shickore, J., & Sugimoto, C.R. (2014). Unpublishable research: examining and organizing the file drawer. Learned Publishing, 27, 253-267. https://doi.org/10.1087/20140404 12. GI Society: Canadian Society of Intestinal Reseasrch. (2011). Andrew Wakefield’s Harmful Myth of Vaccine-induced “Autistic Entercolitis”. Badgut. https://badgut.org/information-centre/a-z-digestive-topics/andrew-wakefield-vaccine-myth/ 13. Kotwani, N. (2007). The Media Miss Key Points in Scientific Reporting. AMA Journal of Ethics, 9(1), 188-192. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCQ.0000277777.35395.e0 14. Wakefield, A.J., Murch, S.H., & Anthony, A., et al. (1998). RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet, 351(9103), 637-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11096-0 15. Wakefield a fake: The MMR vaccine and autism: Sensation, refutation, retraction, and fraud https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3136032/ 16. BMJ: Wakefield Paper Alleging Link between MMR Vaccine and Autism Fraudulent. (2011, Jan 6). The History of Vaccines. Retrieved from https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/blog/bmj-wakefield-paper-alleging-link-between-mmr-vaccine-and-autism-fraudulen 17. Gerber, J.S. & Offit, P.A. (2009). Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses. Clin Infect Dis. 48(4):456-461. https://doi.org/10.1086/596476 18. Jenny McCarthy. (2021 Mar 5). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jenny_McCarthy&oldid=1009414878 19. History of Anti-vaccination Movements. (2018, Jan 10). The History of Vaccines. Retrieved March 5, 2021, from https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/history-anti-vaccination-movements 20. Andrew Wakefield. (2021 Mar 9). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Andrew_Wakefield&action=history 21. History of Anti-vaccination Movements. (2018, Jan 10). Ethical Issues and Vaccines. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/ethical-issues-and-vaccines 22. Vageesh, J. (2019, Nov 15). Mandatory vaccination is not the solution for measles in Europe. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/mandatory-vaccination-is-not-the-solution-for-measles-in-europe-126946 23. Jacobson v. Massachusetts. (2021, Mar 5). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jacobson_v._Massachusetts&oldid=1002758081 24. Ten threats to global health in 2019. (2019). The World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

Leave a comment