THE INITIAL AND POWERFUL MOMENT OF DOUBT

It starts with a niggling feeling. People have called intuition that quiet inner voice, or one’s “gut feeling”. It is an uneasiness passing through a dark alley late at night, or that “A-ha!” moment when unrelated things connect in an unpredictable – but not undetectable – way. We rely on our “nigglings” to tie together accumulated experiences with earlier considerations and when activated towards something not immediately rational, these gut feelings are enough to tip the balance towards belief.

Psychology Today defines intuition as, “hunches…generated by the unconscious mind rapidly sifting through past experience and cumulative knowledge” (https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/basics/intuition). In addition, this same source states that “Scientists have repeatedly demonstrated how information can register on the brain without conscious awareness and positively influence decision-making and other behavior.”

Intuition, however, is not always a GOOD influence. It also plants the seed of doubt that shapes a nascent belief and even forms conclusions before the rational, conscious mind can catch up. Because our gut feelings have been nurtured in our formative years by our parents and our culture, and because they have been credited with life-saving moments or sparks of inspiration, intuition is granted a free-pass to our decision-making process despite the short-cuts it takes.

And therein lies the problem.

Medical science unravels complexity within biological systems that are, quite simply, NOT intuitive. In the realm of science, most people cannot claim to have inner sight. There are gifted scientists who have the ability to recognize patterns and postulate hypotheses (i.e., who can “connect-the-dots”) better than others, but only after delving into a particular scientific realm to a degree that confers expert status. Newton, Darwin, Einstein, Curie, Pasteur – these scientific giants were not casual scientists. Intuition in this realm is carefully cultivated and rewarded only after repeated experimental verification.

In the scientific arena, a rational and intellectual approach reveals truths at which intuition can only guess. Scientific discovery offers evidence (not feelings) when someone asks for proof, shows repeatability (not heresay) when someone asks for confirmation, and provides explanations with predictive capabilities (not excuses or prophecies) when someone seeks understanding.

Contrast the scientific research field with the practice of medicine. Medicine is an art performed (or “practiced”) by those with a healing touch, whether they are trained or indoctrinated in the field, ranging from medical school graduates to witch doctors, those who ‘channel’ healing with an emotional, spiritual, or metaphysical focus and those who manipulate and operate purely in the physical realm. Intuition and a spontaneous judgment in this field can be positive enough to confer the healer with great respect, if only sporadically correct or provided only in a single occurrence.

“A desire to take medicine is, perhaps, the great feature which distinguishes man from other animals.”

Sir William Osler

In this way medical practitioners claim a respect bordering on idolatry in almost all cultures. Moreover, to be healed is the ultimate, personal reward for trust placed in healers. Such emotional devotion has little to do with rational understanding, and patients operate under the assumption that the doctor knows what they are doing, such that they can submit to treatments that may be even more painful or damaging than the disease itself. The decision to trust is to rely on the doctor’s intuition, not one’s own and can, quite literally, be the difference between life and death.

To Believe or Not to Believe

The dichotomy inherent in healthcare comes down to either faith in our healers in whom we are taught to trust with our lives or intellectual support of science that we don’t often understand at a deep level.

“When you reach the end of what you should know, you will be at the beginning of what you should sense.”

Khalil Gibran, Sand and Foam

Most people would agree with the quote, above, but its basis is wrong:

When addressing something you should—and indeed could – know but don’t, the impulse is to ‘go with your gut’. That’s the point when reasoning gets thwarted.

The chasm between understanding WHAT works to heal and WHY it works often defies common sense. It is in this chasm that two very different mindsets lie. One viewpoint relies on intuition and views health and the art of medicine as a personal endeavor. They can be called the Medical Intuitists. The other ideologic framework respects rational exploration and prioritizes population health as a way to ultimately benefit the individual. They can be called the Medical Rationalists. These two mindsets are outlined in the table, below.

How these mindsets skew thinking about advances in medicine, and in particular, population health, has great consequences for adopting preventative health behaviors. Medical Intuitists channel a natural skepticism of medical advances to reject genetically modified fruit, for example. The organics movement responded to this distrust and has fostered a traditionalist viewpoint that eschews additives as foreign and potentially dangerous. People are warned to not eat anything with unfamiliar and often multi-syllabic names because of their supposed chemical and non-natural origins. In contrast, Medical Rationalists trust in: 1) the scientists who have developed genetically-modified fruit, and; 2) in the scientific and regulatory bodies that assess the population safety of these scientific advances. Medical Rationalists hesitate to discard science they do not understand because of a considered reliance on the experts and an expectation of improved health not just for themselves, but for their community.

In recent years, the bitter condemnation of one side by the other has caused a volatile situation. Smear/sneer campaigns on social media illustrate the depth of emotion and fuel further resistance to change. Sadly, it is faster and easier to discredit practices than to build sound logical arguments. Social media’s snapshot approach to communication amplifies the Medical Intuitists’ megaphones. Unfortunately for the naïve information consumer, this is occurring just as conspiracy theories are also gaining in popularity and as misinformation dilutes facts. Less vocal or at least less vocally-persuasive are the Medicial Rationalists who must build a case for science rather than tear it down. However, their culpability lies in their quickness to: a) disparage those who are scientifically-uninformed; b) denounce as spurious those non-statistically significant adverse events when they might be real and rare, and; c) ‘flip-flop’ by embracing new scientific schools of thought that seem to reverse earlier thinking. The debate between sides lacks an arbitrator, although Medical Rationalists would point to the world as the scientific arena with disease amplification or reduction as the endpoint. Medical Intuitists sense that social and political acceptance of new medical behaviors hinge on the force of arguments, despite the fact that the loudest voices rarely claim all merit.

The Advent of Vaccines in Medical Practice

The rise of the practice of vaccination to prevent disease rather than treat disease initiated a furor in an unprecedented way. For the first time, an invasive medical procedure offered protection of a healthy individual. Human kind has evolved to respond to threats and has cultivated an inner sense or intuition about danger, yet our intellect can override this protective impulse. Indeed, the phrase “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” has been passed down through generations to remind us to think rather than react. It takes a particularly conscious effort to decide on a preventative action like vaccination when the decision to act must trump the decision to react. More than that, though, the decision to act must also override that initial and powerful moment of doubt. With the advances in scientific understanding, it is knowledge, not intuition, that is life-saving.

“You can conquer almost any fear if you will only make up your mind to do so.”

Dale Carnegie

Two ideologic frameworks surrounding vaccination:

| Medical Intuitists | Medical Rationalists | |

| –rely on intuition and a focus on self -adhere to holistic, natural health philosophies | –rely on reasoning and on a trust of experts -adhere to scientific principles for population health | |

| 1 | Say: “Don’t fix what ain’t broke.” | Say: “An ounce of prevention is worth an pound of cure.” |

| 2 | Fear preventable disease being imposed on a healthy individual. | Accept the premise of vaccines: that the risk of naturally-occurring disease is worse than the risk of disease associated with treatment. |

| 3 | Fear side effects of vaccination. | Understand and accept risk/benefit ratio arguments. |

| 4 | Believe the MMR vaccine can cause autism and/or the DTP vaccine can result in SIDS in infants. | Trust scientific literature and/or accept conclusions from agencies devoted to scientific advancements and population health safety. |

| 5 | Note that vaccinated individuals still get disease. | Cite that no vaccine is 100% effective and that unvaccinated individuals get disease at a much higher rate than vaccinated individuals. |

| 6 | Are influenced by personal anecdotes: “My neighbor’s kid got sick after his shot!” Believe that one personal anecdote outweighs multiple, conclusive clinical trials. | Refrain from natural human empathy to insist that 1) facts trump emotions, and; 2) statistics make emotional pleas irrational. |

| 7 | Focus on personal attributes and holistic attitudes: “I don’t get sick,” and, “my body will be more strengthened with natural exposure to disease.” Believe that their bodies will respond differently than the majority of people;Feel entitled to individual choice at the cost of others. | Focus on a record of success of vaccines across the world and throughout recent history. Believe in scientific progress for advancing personal health;Find empowerment in supporting group health. |

| 8 | Trust that improved sanitation and hygiene will prevent infectious disease. | Cite the risk and resurgence of infectious disease in under-vaccinated countries. |

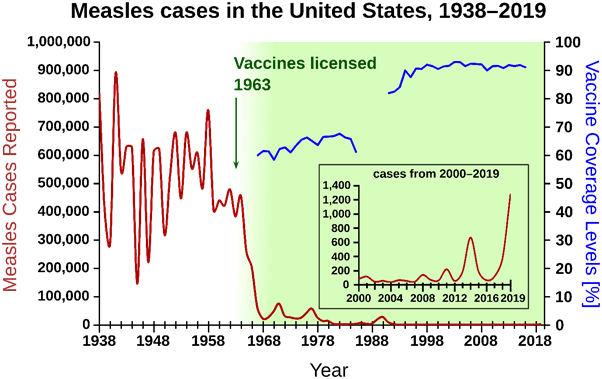

| 9 | Assume that no or low level disease means that there is no need to continue vaccinating. | Point out that diseases stay eradicated in a community as long as vaccines are used to prevent reoccurrences. |

| 10 | Distrust that the human body can handle the chemicals in a vaccine. | Learn that human bodies are assaulted with many more environmental and chemical insults everyday than are in a vaccine. |

| 11 | Reject vaccines as an artificial way of stimulating the immune system: “Injection is a foreign way to introduce disease pieces to my body.” | Accept scientific progress demonstrating that vaccination is an effective and efficient way to initiate an immune response. |

| 12 | Cite religious beliefs: “God alone decides who gets sick and who lives and dies.” | Cite the secular axiom: “God helps those who help themselves,” while referencing survival statistics associated with vaccinated populations . |

| 13 | Prioritize personal freedom above group health: Adhere to the idea: “My health, my choice.”Reject the idea of mandatory vaccination. | Prioritize individual and community safety: Adhere to the idea: “Protect myself, my family, and my community.” Agree that schools, employers, and even governments have the right to insist on protecting their student body / employees / citizens and can ask individuals who do not vaccinate to remove themselves from endangering others by not participating in society. |

| 14 | Distrust “Big Pharma”. | Look to larger pharmaceutical companies to afford and have the expertise to do the research, development, and testing of vaccine candidates and to federal regulatory agencies to safeguard population health by overseeing “Big Pharma”. |